But does trouble lie in store when it comes to AI art?

The Uffizi gallery in Florence revealed that it has commenced legal action against Jean Paul Gaultier.

The French luxury fashion brand used images of the museum’s famous painting Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli in its Le Musée collection.

The Uffizi Gallery’s director Eike Schmidt claimed in a statement that it is illegal to use the gallery’s artwork without permission. This, he says, is thanks to Italy’s cultural heritage laws which require anyone using an object of cultural interest for commercial purposes to obtain permission and pay a fee that will be determined.

Broadly this includes any object belonging to a public body or a non-for-profit private legal entity made over seventy years ago by an author or creator who is a deceased person or has been granted such a status by Italy’s Ministry of Cultural Heritage.

As Schmidt puts it: “if anyone wants to use this material, they must make a formal request, [and] if the request is granted, then they have to pay” – a succinct summary of the effect of Articles 107 and 108 of the country’s Cultural Heritage Code (CHC), which some have described as “pseudo-copyright“.

The Uffizi’s legal action follows its legal threat to Pornhub over the adult site’s inclusion of the gallery’s raciest works in the porn platform’s guide to the most explicit artworks top Western art galleries. Pornhub was quick to back down, removing anything classed as a piece of Italian cultural heritage from its “interactive guide to some of the sexiest scenes in history”.

What is striking about all this is the ease with which Italian cultural heritage laws have avoided any more complicated discussions about copyright and have preserved a valuable revenue stream for the country’s museums and galleries through public law mechanisms.

This has prevailed even in the face of new developments in art such as the rise in popularity of digital art and non-fungible tokens (NFTs). The Uffizi had been collaborating with the Milan-based company Cinello to produce digital versions of its artworks with an agreement to split the proceeds 50/50.

But the use of Artificial Intelligence to generate images now raises more challenging questions about how the CHC should be applied to the likes of Google’s Imagen, Open AI’s DALLE-2 and MidJourney. Let’s break this down a bit.

AI image generators will only be in breach of Italy’s CHC if the AI generator has not been granted permission to reproduce an image classed as Italian cultural heritage.

This stands regardless of whether the use of the reproduction is for profit or meets one of the exceptions to the requirement to agree a fee with the relevant cultural institution listed in Article 108 (3(2)) CHC: “a non-profit basis, for purposes of study, research, free expression of thought or creative expression, promotion of knowledge of cultural heritage”. Even where no fee is required (as per Art. 108 (3(2)), applicants are expected to reimburse any costs incurred in the process of granting the permission.

So, it appears that these AI companies may have to make a call to the relevant Italian art galleries, especially since many have begun to commercialise their tools. But this will only be the case if AI generators are using a reproduction of the artworks.

What’s most intriguing about this is not whether there has been a reproduction, but how many times an image may be considered to have been reproduced.

If a reproduction is included in the dataset used to train the AI, then there could be a breach in relation to the input. But what about the output for an image that is produced? This is complicated by the fact that the popular diffusion model for producing these images does not use an exact reproduction.

It is hard to get an indication on this point from the case law and I have found it difficult (perhaps unsurprisingly) to track down the offending images in order to consider to what extent they have been edited.

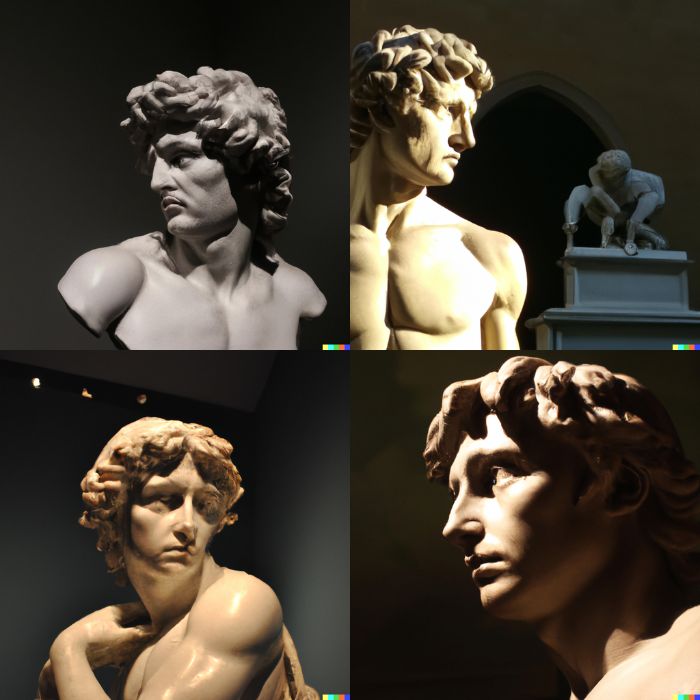

There are three principal cases to look to for guidance. First, in 2017 the Court of Florence ordered the travel agency and tour operator Visit Today, which had reproduced the image of Michelangelo’s David statue in its advertising to remove all images of Michelangelo’s statue of David from its digital and print promotional material and publish the decision in three national newspapers and on Visit Today’s website.

In the same year, the Court of Palermo found that an Italian bank had breached the CHC when including an image of the city’s Teatro Massimo in their adverts. Most recently, the Court of Florence issued an injunction against Studi d’Arte Cave Michelangelo S.r.l. for using an image of Michelangelo’s David.

But there is little in these cases on the point at which something may be considered a reproduction. Do the style, the tone, or the artist’s recognisable traits matter? Looking at the IP academic Andres Guadamuz’s images generated on MidJourney from the command ‘Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh’ may allow you to better visualise the problem.

To further complicate matters, without guidance from a court, Italy’s many and various cultural institutions will exercise the power to chose how they apply the CHC which may open up inconsistencies.

This is certainly something for Italian cultural heritage lawyers to ponder in the future. But, for now, here’s some example of the output that DALLE-2 has produced of Italian heritage that fallen foul of these law (Michelangelo’s David), so that you can ponder that question too!