A perfect 1920s murder mystery is explored in a compelling narrative by journalist and author, Stephen Bates

Early in 1921, Katharine Armstrong, wife of a country solicitor, Herbert, was found dead following an illness. Her doctor at the time gave the cause to be natural. But over a year later, her body was exhumed, traces of arsenic identified in her body. Herbert Armstrong was arrested, tried and hanged for poisoning her, the only solicitor in England to be so executed.

Stephen Bates’ gripping tale, The Poisonous Solicitor, reveals how Armstrong went from respectable lawyer, clerk in the magistrate’s court and church warden, to being at the centre of one of the most celebrated murder trials of the time, each day recounted in newspaper reports which made their way around the world, and ultimately became a convicted murderer, hanged at Gloucester Prison on 31 May 1922, a hundred years ago to the day.

Putting aside that there’s a solicitor at its heart, Bates’ account is a perfect book for lawyers because it combines a compelling re-enactment of the trial, with all the vital ingredients of a courtroom drama, and at the same time, as it is not at all clear that Armstrong did, indeed, poison his wife, the story feels like you are reading your own whodunnit.

Described by one American newspaper as a “the greatest poison drama of the century”, it was, of all things, a conveyancing transaction that was the beginning of Armstrong’s downfall. In 1921, he had been acting for local landowners in a land dispute. A rival solicitor, Oswald Martin, acted for the opposing tenant farmers.

The issue had become protracted, and (as conveyancers will readily relate to) feelings were running very high. Armstrong and Martin had a meeting over a tea which included scones (remember: this was a hundred years ago!), one of which Armstrong was said to have proffered Martin. Later that day, the rival solicitor then became very ill, and his family accused Armstrong of attempting to poison Oswald Martin with the scone. This accusation set in motion a chain of events that led to Armstrong’s wife’s body being dug up and examined by the most eminent pathologist of his day, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, and Armstrong’s eventual arrest.

The first half of the book is a slow-burn towards Armstrong’s committal hearing, the second half, the grisly trial itself. Bates scatters seeds of doubt of Armstrong’s guilt over the course of the narrative and his account of the two-week trial portrays a “seriously flawed” process which lets those doubts flower.

Plus the court case has everything for the lawyer-reader: there is the evidence, such as the arsenic found in Armstrong’s jacket pocket which he says he was using as weedkiller for the dandelions in his garden, the testimony of servants such as the housekeeper and the nurse that cared for Katharine up to her death. We hear from the expert witnesses: the pathologist, a toxicologist, and so on. There are suspicions that one of the defence witnesses is “turned” as she changes her story between committal proceedings and the full trial.

There is a prosecuting barrister, Sir Ernest Pollock, who was also Attorney-General. This turns out to be crucial later on when there are attempts to get the murder conviction appealed to the Law Lords, (the final appeal court at the time). The person whose job it was to decide whether an appeal could go ahead was, in fact, the Attorney-General himself. There is an exasperated, hard-working defence barrister, Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett, whose special mode of questioning a witness was known in legal circles as “doing a Curtis”. Pivotal in the trial is the presiding Judge Darling. Bates labels him: “the fourth lawyer on the prosecution side” because his repeated interventions always favoured the prosecution’s case.

The detail all through this book is remarkable and sometimes funny. For instance, Armstrong got a third from Cambridge and trained to become a solicitor at the firm Alsop, Stevens and Crooks. The law firm he went on to establish in Hay is still there, as is Armstrong’s swivel chair, desk and pipe. Armstrong’s own solicitor, Tom Matthews, stood by his client right to the end (no wonder then that his costs and disbursements amounted to the equivalent of £200,000. There was no such thing as legal aid) and his firm is still in Hereford to this day.

Of course, we know with terrible finality where this story ends: with the ‘Black Cap’ and the noose around Armstrong’s neck. Bates can even report the thoughts and observations of the executioner, John Ellis, who mentions the solicitor’s final days in his published memoirs, Diary of a Hangman. The Poisonous Solicitor has all the raw material the reader needs to make up their own mind as to Armstrong’s guilt; as long as they read right to the end where Bates leaves us with a fascinating twist in this Agatha Christie-esque murder mystery.

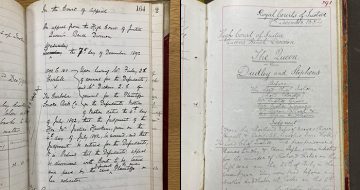

Author, Stephen Bates, is doing an online Q&A with the National Archives, where some of the documents relating to Armstrong trial are kept, on 8 June.