She was represented at son’s inquest by legal dream team she met on Twitter

Baroness Helena Kennedy, a silk at Doughty Street Chambers, is not someone I’ve ever claimed to have anything in common with. But now, having read in her foreword to Justice for Laughing Boy that she “wept when [she] read this powerful book”, I can say that I do.

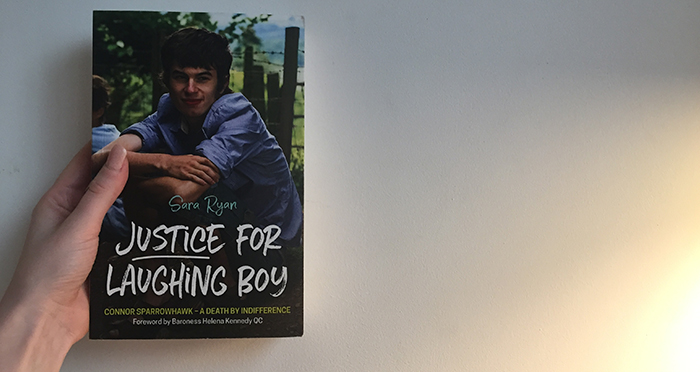

The story of a young man, Connor Sparrowhawk, found dead while under the care of an NHS trust, this 2018 title is beyond your typical read-by-the-beach weepy. For starters, it’s true. And, particularly poignantly, it’s written by Sparrowhawk’s mother, Sara Ryan, who is an academic at the University of Oxford.

Justice for Laughing Boy is many things. Particularly in the first half of the book, much reads like an extended eulogy to Sparrowhawk — “a strong defender of human rights” whose passion for buses, N-Dubz, The Inbetweeners and mermaids demonstrates his quirky loveableness.

But, sadly, Justice for Laughing Boy is also a public record of Ryan’s herculean battle against the authorities following her son’s autism diagnosis.

Banned from a local primary school and faced with paediatricians’ “relentless focus on deficit”, as Sparrowhawk approached adulthood he became “uncharacteristically unhappy and anxious”, even turning violent on occasion.

Ryan tried desperately to seek effective support for her son, but grew increasingly frustrated at learning-disabled persons’ place “very much near the bottom of, or at the bottom of, the support pile”. She was faced, recurrently, with “mother-blame” as a response to her concerns; calls to crisis lines, GPs and more saw Ryan “almost gnawing on the phone in despair”. She began documenting her struggles on her blog, My Daft Life, where she was met with similar stories from the parents of other learning-disabled children.

Pondering a question posed on my blog this week: 'Why didn't you just take him home?' The blame stain is a persistent one. #JusticeforLB

— Sara (@sarasiobhan) January 21, 2018

In spring 2013, Sparrowhawk was moved to a short-term assessment and treatment unit run by Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, where he would be observed and assessed over a few weeks “to work out why he was so distressed and unpredictable”. While there, Sparrowhawk lunged at a support worker, was pinned face down to the floor by four staff, and sectioned under the Mental Health Act. More than 100 days later, in July 2013, Sparrowhawk suffered an epileptic seizure while taking a bath. He had been born in a bath and had died, aged 18, in a bath, too.

Ryan was staggered by the level of negligence demonstrated by the trust, not least because her son, a diagnosed epileptic, was left unsupervised and locked in a room while bathing. It even came to the fore that a 57-year-old man had previously died in the same bath as Sparrowhawk and in the presence of some of the same staff members — and that a nurse on shift while Sparrowhawk was in the bath had being doing an online shop. “A death by indifference,” Ryan says.

Since Sparrowhawk’s death, Ryan, her family and supporters have spent years fighting their #JusticeForLB campaign, which has won Liberty’s ‘Close to Home’ award. Utilising the law effectively is perhaps one of the most vital components to Ryan and co’s mission. Yet, as Kennedy says in her foreword, Justice for Laughing Boy is a story that “lays bare the deep inequities within our legal system”.

This is perhaps most striking at the inquest into Sparrowhawk’s death. Facing seven separate legal teams on the other side, Ryan rubbishes the then Minister for Justice and Civil Liberties’ claim that inquests “are specifically designed so people without legal knowledge can easily participate” as “utter bollocks”. She continues:

“There were no wigs and gowns… but the context, the setting, the process and the enormity of the whole thing was overwhelming.”

Fortunately, and vitally, Sparrowhawk “had the very best fighting in his corner”, in the form of: Bindmans’ Charlotte Haworth Hird, Brick Court Chambers‘ Paul Bowen QC, Doughty Street’s Caoilfhionn Gallagher (now QC) and her new pupil, Keina Yoshida. (The Sparrowhawk inquest took part in the first two weeks of Yoshida’s pupillage, what an interesting case to start off with.)

Speaking to Legal Cheek, Bowen explains how this legal dream team was assembled:

“I’ve done a number of high-profile cases involving the rights of disabled people and I’d been following Sara’s blog and also on Twitter; it was through Twitter I found out Connor had died.”

Bowen, who has acted for right-to-die campaigners Debbie Purdy and Tony Nicklinson, continues:

“Given my legal background, I felt I’d be able to help so I reached out to Sara on Twitter, and Caoilfhionn did the same. It was Caoilfhionn who put the family onto INQUEST [a charity providing advice on state-related deaths], who then put them onto Bindmans. It wouldn’t have happened without Twitter.”

Ryan couldn’t speak more highly of her legal team, who “led the proceedings from start to finish with expertise and an apparently instinctive grasp of what battles were important to fight and what to leave”. Gallagher and Haworth Hird “demonstrated speed, skill and expertise in digging through tomes of case law to provide additional evidence”, while Ryan commends Bowen’s “polite, missile-like points”.

But, even with a stellar legal team, navigating the two-week jury inquest was far from easy. “From the moment Connor died, it felt like a well-oiled machine, involving the Southern Health in-house and external legal representatives, was cementing a wall of denials,” Ryan reflects. “In our two years of interactions with our legal team… they had always been brutally open about what a mountain climb we were facing in this process.”

Ryan continues to climb that mountain. Justice for Laughing Boy, which is soon to be made into a film, ends:

“I hope this much-needed conversation has started. We all have a responsibility to drag the UK out of a learning disability ‘care’ space that seems to remain aligned closer to the eugenic practices of the last century than a so-called advanced, civilised society.”