Bristol University student and future trainee William Holmes explains how the Italian Renaissance has informed modern IP law

On 19 June 1421, the Republic of Florence granted Filippo Brunelleschi a three-year exclusive right to build and make use of his new type of boat “Il Badalone” on the river Arno in Florence. Although Brunelleschi’s boat did not survive its first outing and sank in the Arno, the legacy of his 1421 patent lives on today. The subsequent developments in intellectual property (IP) rights amongst the Italian city states are considered to be the progenitors of modern IP law. The Italian Renaissance’s principal heritage is embedding the concept of human ‘genius’ into our understanding of authorship and inventorship.

These foundations are now being shaken by recent technological innovations. Artificial intelligence (AI) has seen machines independently create art, music, literature and several useful inventions. The rise of the machine author and inventor has raised questions about whether a patent should be granted or copyright protection should subsist for machines’ creative productions. So, to what extent do we owe these IP problems to the Renaissance? Are there insightful parallels between the Renaissance’s development of IP and our present situation? And is it time to break with the past and redefine our IP laws?

Authorless and inventorless

For copyright to subsist under the UK’s Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988 (CDPA), a work must be original. The test for originality (both before and after the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) Infopaq decision) is inextricably linked to authorship; the author is the legal person responsible for the original elements of a work. At present, AI cannot be considered an author because it does not have legal personhood.

The CDPA, however, was the first piece of legislation that introduced provisions for copyright protection in computer-generated works. The CDPA, in section 178, defines computer-generated works as works where there is no human author and provides a solution to this absence of human authorship in section 9(3). The author of a computer-generated work is “the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”.

This, however, raises the question of whether the person (or persons) making the necessary arrangements for the creation of the work can meet the standard of originality required of an author, considering that they are only facilitating the AI’s creativity. Perhaps the efforts of making such arrangements is enough? Or, alternatively, can we objectively assess an AI’s originality compared to human standards? This remains to be tested in court.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreSimilar issues arise surrounding inventorship and legal personhood in patent applications for AI inventions. As I explain at greater length here, whilst an AI could satisfy the definition of an inventor, its lack of legal personhood is again problematic. This is because inventorship is inextricably connected to ownership (the inventor is the owner of a patent by default). But in order to be able to own or assign ownership to someone, AI would need to have legal personhood.

The lawyers working on the Artificial Inventor Project are currently testing this by filing patent applications for the creativity machine DABUS’s inventions in several different jurisdictions. The most promising sign the project has received was when the High Court’s 2020 ruling noted that “DABUS has “invented” the inventions” and the law may “cater for future developments, including developments that were — until they surfaced in litigation — unforeseen”. However, for now, AI’s creations remain authorless and inventorless in the eyes of the law.

From ars to ingenium

Underlying these issues is a broader question: why should IP law only reward human creations? The reason we are asking this today is, in large part, thanks to the way IP law was developed in Renaissance Italy.

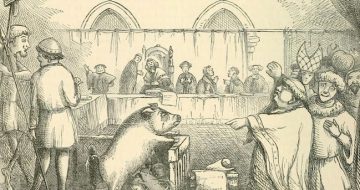

Intellectual property law in the Italian city states was born out of two tensions. The first was a clash between the guild communes and talented entrepreneurial individuals. The guild communes (groups that specialised in certain crafts such as glass-making) passed on craft knowledge through apprenticeship schemes. On becoming an apprentice, you were forced by the guild to take an oath of secrecy that would prevent you from spreading guild knowledge to rivals. City states vigorously enforced this. Florence and Venice threatened those who fled the city’s guilds with capital punishment, whilst the cities of Lucca and Genoa would richly reward anyone who murdered a fugitive artisan.

Ironically, this protectionism created an attitude of ownership towards the intangible property of craft knowledge. Unwittingly, the guilds had developed the concept of intellectual property. And disparities in knowledge and ability eventually gave rise to individual entrepreneurs like Brunelleschi who refused to abide by the guild system.

The second tension was between man and machine. Society redefined the nature of its abilities in the face of cheap mass production. Under the sway of Renaissance humanisms’ focus on the individual, many types of craft knowledge came to be “treated as forms of ‘knowledge’ rather than mechanical skill”. Ars (mechanical skills collectively practised within guilds) became ingenium (forms of knowledge in an individual’s mind). The focus shifted from the collective and mechanical to the individual genius of the mind.

Accordingly, Brunelleschi argued in his patent request that he should have exclusive rights to his boat on the grounds that the machine was “the fruit of his genius and skill”. Similarly, the 1474 Venetian patent statute granted monopolies for “any new and ingenious device”, explaining that it aimed to attract individuals “who have the most clever minds, capable of devising and inventing all kinds of contrivances”. This justification for IP rights that centred on the unique genius of an individual’s mind has evolved into our concepts of authorship and inventorship.

The death of the author?

The DABUS case has highlighted the limited nature of this definition. As the High Court ruling explained: “To take a somewhat extreme example, were an alien from outside the galaxy to present itself before the courts of England and Wales, I would like to think that it would not be denied legal personality simply on the grounds of unforeseen extraterritoriality. The courts are well able to differentiate between an alien artefact (say a meteorite, a thing) and an alien (which if capable of interacting as a natural person, is or ought to be a person).” But the trajectory that Brunelleschi’s patented boat set IP law on is now preventing this natural progression for the innovations of our time. However, just as new technology redefined Renaissance Italy’s notion of authorship, will AI now redefine our understanding of authorship and inventorship?

There are two things that the Brunelleschi’s patented boat can teach us. First, that our understanding of what being an author or inventor means is based on a 600 year-old definition. Second, that a society’s interaction with new technology inevitably redefines the society’s understanding of itself. It remains to be seen if the birth of creative AI will be the death of our 600-year-old author and the inventor. If so, perhaps then copyright can subsist for AI works and patents can be granted for AI inventions.

William Holmes is a penultimate year student at the University of Bristol studying French, Spanish and Italian. He has a training contract offer with a magic circle law firm.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.